- Research article

- Open access

- Published:

Association of military life experiences and health indicators among military spouses

BMC Public Health volume 19, Article number: 1517 (2019)

Abstract

Background

The health and well-being of military spouses directly contribute to a robust military force by enabling the spouse to better support the active duty member’s career. In order to understand the overall health and well-being of military spouses, we assessed health indicators among military spouses using the Healthy People 2020 framework and examined associations of these health indicators with military experiences and psychosocial factors.

Methods

Using data from the Millennium Cohort Family Study, a U.S. Department of Defense-sponsored survey of 9872 spouses of service members with 2–5 years of military service, we examined attainment of Healthy People 2020 goals for spouses and service members, including healthy weight, exercise, sleep, and alcohol and tobacco use. Multivariable logistic regression models assessed associations of spouse health indicators with stressful military life experiences and social support, adjusting for demographics and military descriptors. The spousal survey was administered nationwide in 2011.

Results

The majority of military spouses met each health goal assessed. However, less than half met the healthy weight and the strength training goals. Reporting greater perceived family support from the military was associated with better behavioral health outcomes, while having no one to turn to for support was associated with poorer outcomes. Using the Healthy People 2020 objectives as a framework for identifying key health behaviors and benchmarks, this study identified factors, including military-specific experiences, that may contribute to physical health behaviors and outcomes among military spouses. With respect to demographic characteristics, the findings are consistent with other literature that women are more likely to refrain from risky substance use and that greater education is associated with better overall health outcomes.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that enhanced social and military support and tailored programming for military spouses may improve health outcomes and contribute to the well-being of military couples. Such programming could also bolster force readiness and retention.

Background

Promoting healthy behaviors and outcomes has long been a priority for the United States military, and since 1986, the Department of Defense (DoD) has emphasized its Health Promotion and Disease Prevention directive, which provides health guidance and encourages healthy living goals among military personnel and their beneficiaries [1]. Health behaviors that put individuals at risk of physical and social consequences are alarmingly prevalent among service members, particularly those involving substance use [2,3,4]. One DoD study found that 39.6% of all active duty current drinkers reported binge drinking in the past month; and 24.5% of active duty service members reported cigarette use in the past month; additionally, 51.2% of active duty personnel were classified as overweight, despite the military’s high physical health standards [3]. Poor health behaviors negatively affect not only the individual, but also their families and broader society, causing an increase in missed days from work and health care costs [5]. The health and well-being of military spouses also directly contribute to a robust military force by enabling the spouse to better support the active duty member’s career [6] and have significant health care cost implications. A study of TRICARE beneficiaries (dependents of active duty personnel, military retirees, and dependents of military retirees) found that each year DoD spends approximately $2.1 billion for medical care associated with obesity, alcohol use, and tobacco use [2].

There is less data available regarding the health of military spouses compared to service members; however, some studies shed light on potential health issues. A 2012 presentation found that one in five Army active duty spouses are overweight, one third are obese [7] and studies suggest that service member deployment is not a predictor of spouses’ overweight or obesity [8, 9]. Approximately 8.2% of military spouses married to service members with 2–5 years of experience reported alcohol misuse [10] and unhealthy alcohol use among military spouses was associated with feeling bothered by communication about the service member’s deployment experiences as well as the spouse feeling stressed by a combat-related deployment or duty assignment [11].

In an effort to combat health disparities and to improve health outcomes for all Americans, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services launched a health promotion program and evaluation measure called the Healthy People initiative [12]. The Healthy People 2010 initiative (HP2010) analyzed 28 different focus areas containing 467 measurable objectives of physical health from 2000 to 2010, and these objectives were updated for Healthy People 2020 (HP2020) [13]. Although research on the U.S. population shows that particular population groups are disproportionally affected by poor health outcomes and have less access to preventive care (e.g., individuals living below the poverty line, individuals in rural populations, and racial/ethnic/sexual minorities) [14,15,16,17,18], there has been very little research investigating the relative achievement of Healthy People objectives among military populations, and particularly military spouses. In a 2006 study, self-reported service members’ health behaviors met or exceeded 7 of the 19 HP2010 objectives assessed, including those related to obesity and exercise [19]. Kress and colleagues assessed HP2010 objectives among military retirees and their spouses and found that fewer retirees and beneficiaries met obesity, exercise, substance use, and healthy eating objectives than national target percentages [20]. Being male, having less than a college degree, and less-than-excellent self-reported health status were associated with a lower likelihood of meeting the objectives [20, 21].

Despite DoD’s commitment to the health and well-being of all members of the military community, military spouses may be at greater risk for poor health behaviors than their military partners or civilian counterparts. Military spouses do not have the same incentives and structure to help them maintain their health, yet they are exposed to many stressors unique to military life, such as relocation and deployment, that may challenge healthy living [22, 23]. Additionally, access to military health promotion programs and support systems that have been shown to reduce poor health behaviors [24,25,26] is uneven, particularly for certain subgroups, such as male and minority spouses and spouses of those serving in National Guard and Reserve components.

In order to understand the overall health and well-being of military spouses, the current study aimed to investigate various health behaviors and indices, including weight, exercise, sleep, and substance use, using data from the Millennium Cohort Family Study (henceforth referred to as the Family Study), which is a probability-based cohort [27,28,29]. We have used the HP2020 goals framework to assess health indicators among military spouses and assess associations between these health indicators, operationalized as attainment of HP2020 goals in several domains, and sociodemographic characteristics, military experiences, and psychosocial factors.

Methods

Sample design and study participants

This analysis used the Family Study baseline sample, which consists of 9872 service member/spouse dyads. The service members are participants in the Millennium Cohort Study who were married and had 2 to 5 years of military service as of 2011. Married and female service members were oversampled in the Millennium Cohort Study to ensure that male spouses of female service members were adequately represented in the Family Study. Spouses of participating service members were then recruited in 2012 to complete the dyads. The sample is unique in that it includes a representative sample of young military couples, from all service branches and components (active duty, military Reserve, and National Guard participants).

The Family Study methods are described in more detail elsewhere [27,28,29]. The Family Study was overseen and approved by the Naval Health Research Center’s Institutional Review Board (Protocol 2000.0007) and the Office of Management and Budget (approval number 0720–0029). Written or electronic informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

Service members and their spouses independently completed surveys addressing various aspects of physical and mental health as well as their health behaviors. Additionally, participants provided permission to merge their survey responses with archival data on their military personnel and medical treatment records. Although the analyses for this paper focused primarily on the spouses’ survey responses regarding health, we did include several predictors and covariates from Millennium Cohort research program data resources, described below.

Health outcomes

Six dichotomous indicators were used to identify spouses who met the HP2020 goals with respect to healthy weight (body mass index; BMI), aerobic exercise, strength training, sleep, alcohol use (risky drinking), and tobacco use (current smoking). The criterion definitions for each of the goals map on closely to the respective HP2020 goals and are detailed in Table 1. For aerobic exercise and strength training goals, spouses who stated that they did not or were unable to physically engage in these types of exercise were coded as not meeting the goals. Service member health indicators were measured in the same manner as the corresponding spouse health measures.

Social support and military stress experiences

Measures of military and social support were included as independent variables. Military support was measured with 2 items: perceived military support for the spouse and their family and perceived military support for the service member. These are both ordinal variables, where 0 = “Poor”, 1 = “Fair”, 2 = “Good”, 3 = “Very good”, and 4 = “Excellent.” Four ordinal items addressed social support for the spouse respondent. One item from the Patient Health Questionnaire (the degree to which you are bothered by not having someone to turn to in the last 4 weeks) had 3 categories (1 = “Not bothered”, 2 = “Bothered a little”, 3 = “Bothered a lot”). Spouses were asked 3 additional questions about social support (having someone to turn to when dealing with personal problems, having someone to tell you honestly how you are handling problems, and how well family and friends have supported you in the last 4 weeks) on 5-point scales (0 = “Strongly disagree” or “Not at all” to 4 = “Strongly agree” or “Extremely”).

Other independent variables included 4 aspects of the stress of military life: deployment stress, injury stress, family stress, and stress resulting from one or more permanent change of station (PCS) moves. For each of first three domains: deployment (e.g., a combat-related deployment or duty assignment for your spouse), injury (e.g., combat-related injury to your spouse), and family stress (e.g., difficulty balancing demands of family life and your spouse’s military duties), the mean of three items was calculated [27]. Each of the items was scored from 0 to 4 (0 = never experienced, 1 = not at all stressful, 2 = slightly stressful, 3 = moderately stressful, 4 = very stressful). The deployments and injuries referred to by these items were experienced by the service member, not the spouse. A single item assessed the perceived stress of PCS moves with the same 0–4 scoring as the other military stress items.

Covariates

In addition to the independent variables listed above, we included spouse sociodemographics and several service member’s military characteristics. Spouses’ self-reported characteristics included gender, age, race and ethnicity, educational attainment, employment status, annual household income, number of children, and prior or current military service. Participants were asked to select from the following race/ethnicity options: White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, Native American, or Other. For analytic purposes, participant were categorized as White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, or Other. Service member military characteristics included pay grade (officer vs enlisted), branch of service (Army, Air Force, Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard), and component (active duty vs Reserve or National Guard). These data were obtained from administrative records provided by the Defense Manpower Data Center.

Analyses

After generating descriptive statistics on the demographics and measures of stress and support, we examined attainment of six HP2020 goals for the spouses and service members by calculating the proportions meeting each goal. Additionally, we examined the concordance of spouse-service member pairs with respect to goal attainment in each domain. Finally, we estimated a multivariable logistic regression model for each spouse health outcome to investigate its unique associations with military life experiences and social support, as well as with the demographic and military characteristics. All social and military support independent variables were used as continuous measures in the models. Adjusted odds ratios can be interpreted as the relative change in odds of a particular spouse meeting a health indicator associated with each additional military stressor experienced or a 1-unit increase in perceived social support. All analyses were weighted to account for the sample design and nonresponse; these weights allow the findings to be generalized to the population of married spouses of service members with 2 to 5 years of military experience [29].

Results

Population description

Most spouses were female (86%) and between 25 and 34 (62.1%) years of age (Table 2). More than 70% were White and 53.2% had some college experience or an associate degree. Approximately two thirds (63%) had at least one child. The vast majority of spouses (80.6%) had no history of military service; 9.4% were currently serving in the military. Half of the spouses’ service member partners served in the Army, followed by 17.4% in the Air Force, 15.3% in the Marine Corps, 14.2% in the Navy, and 2.8% in the Coast Guard.

Healthy People 2020 objectives

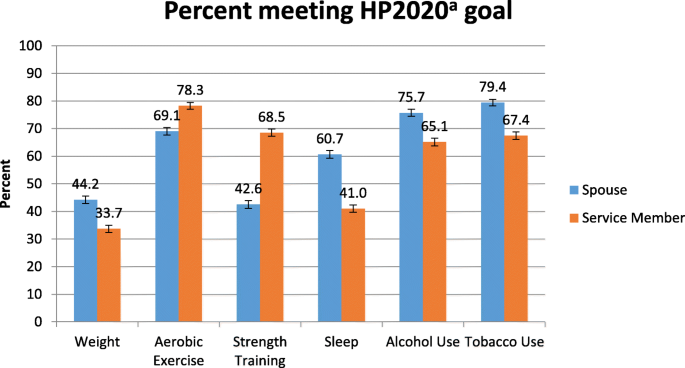

Figure 1 shows HP2020 goal attainment by military spouses and service members. Overall, the majority of spouses and service members met each of the HP2020 goals analyzed (as defined in Table 1). More than half of the responding spouses met the goals related to aerobic exercise (69.1%), sleep (60.7%), alcohol use (75.7%), and tobacco use (79.4%). Only 44.2% of spouses met the healthy weight/BMI goal: 3.0% were underweight, 29.1% were overweight, and 23.7% were obese. Only 42.6% of spouses met the strength training goal of 2 or more days a week. More than half of the responding service members met the goals related to aerobic exercise (78.3%), strength training (68.5%), alcohol use (65.1%), and tobacco use (67.4%). Only 33.7% of service members met the healthy weight/BMI goal and only 41% met the sleep goal. Goal attainment was more prevalent for spouses in weight, sleep, alcohol use, and tobacco use, and more prevalent for service members in aerobic exercise and strength training. Table 3 shows the pairwise agreement of couples with respect to each of the health indicators. All show modest agreement, with concordance percentages ranging from 51 to 73% and kappa coefficients ranging from 0.06 to 0.31 (all p < 0.001); dyadic concordance was strongest for alcohol and tobacco use goals.

Percent meeting HP2020a goal. Caption: HP2020 Goal Attainment for Family Study Spouses and Service Members. Refer to Table 1 for HP2020 goal definitions. Sample sizes vary across goals due to missing values. Sample sizes for spouse goal attainment are 9764 (weight/BMI), 9031 (aerobic exercise), 9655 (strength training), 9588 (sleep), 9469 (alcohol use – risky drinking), and 9762 (tobacco use – smoking). Sample sizes for service member goal attainment are 9814 (weight/BMI), 9394 (aerobic exercise), 9662 (strength training), 9756 (sleep), 9260 (alcohol use – risky drinking), and 9475 (tobacco use – smoking.). Footnote: aHealthy People is a national study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Years of data for Healthy People 2020 range from 2005 to 2015

Multivariable analyses of health behaviors

The multivariable analyses regressing spouse health outcomes on support and military life stressors are shown in Table 4. Of the 6 social and military support independent variables examined, only 2 were statistically significantly associated with any of the HP2020 goals analyzed. Spouses reporting being more bothered by having no one to turn to were significantly less likely to achieve the HP2020 healthy BMI, sleep, risky drinking, and current smoking goals. More specifically, a 1-unit increase in the degree to which spouses were bothered (e.g., from “Bothered a little” to “Bothered a lot”) was associated with a 27% decrease in the odds of meeting the healthy weight/BMI goal, a 32% decrease in the odds of meeting the sleep goal, a 31% decrease in the odds of meeting the risky drinking goal, and a 37% decrease in the odds of meeting the smoking goal. A greater level of perceived support by the military to help the spouse and their family was associated with a higher likelihood of the spouse meeting the sleep goal. Specifically, a 1-unit increase in perceived support from the military to help the spouse and their family (e.g., from “Fair” to “Good”) was associated with a 21% increase in the odds of the spouse meeting the sleep goal.

Of the 4 types of military stressors included in our models as predictors (deployment, injury, family, and PCS), only deployment-related stressors were marginally significantly associated with any of the spouse health indicators. A one-unit increase in stress related to deployment experiences (e.g. from slightly to moderately stressful) was associated with an 8% increase in the odds of spouses meeting the HP2020 BMI goal.

Spouse demographic characteristics

Female spouses were much more likely than male spouses to meet the HP2020 goals for weight as well as both alcohol and tobacco use, with more than twice the odds of meeting the weight and tobacco use goals. Female spouses were considerably less likely to meet the strength training goals. Older spouses, and in particular those over age 35, were less likely to meet the healthy weight goal. Those aged 35 and older were also less likely to meet either of the exercise goals but more likely to meet the alcohol use goal. Compared to Whites, Black non-Hispanic spouses were less likely to meet the weight, aerobic exercise, and sleep goals but much more likely to meet the tobacco use goal. Those of other races were also less likely to meet the aerobic exercise goal but more likely to meet both of the substance use goals. Greater educational attainment confers greater likelihood of meeting each of the HP2020 goals, except for sleep for which there was no association. In general those with a college degree had better outcomes than those with some college, who in turn did better than those with no college. In particular, those with at least a bachelor’s degree had 3.5 times the odds of those with no college of refraining from tobacco use. Those identifying as homemakers or students were more likely to meet the alcohol use goal than other employment groups; no other associations between spouse employment status and meeting the HP2020 goals were observed. Spouses with children were less likely to meet the weight, exercise, and sleep goals but more likely to meet the substance use goals. Compared to those with no personal military experience, spouses who were themselves current members of the military were much more likely to meet both exercise goals than non-military spouses; however, they were less likely to meet the sleep goal. Spouses who were formerly in the military were also less likely to meet the HP2020 goal for sleep and also less likely to meet the goal related to risky alcohol use.

Service member military characteristics

Spouses of military reserve or National Guard members were less likely to meet the strength training goal, but no other differences with respect to military component were observed. Spouses of officers were more likely to meet the weight and aerobic exercise goals and also had more than three times the odds of meeting the tobacco use goal compared to spouses of enlisted soldiers. Compared to the spouses of service members in the Army, spouses of Air Force members were more likely to meet the sleep goal as well as both substance use goals. Marine spouses were less likely to meet the risky alcohol goal but more likely to not use tobacco. Navy spouses were also more likely than Army spouses to meet the tobacco use goal.

Discussion

Overall, the majority of military spouses and service members met most of the HP2020 goals analyzed in the study. However, less than half of military spouses met the healthy weight/BMI goal or the strength training goal. Spouses were more likely to achieve healthy weight, sleep, and alcohol and tobacco use goals than were service members, whereas more service members met the aerobic exercise and strength training goals likely due to physical health demands of military service. In addition to comparing military spouses with their partners, it is important to contextualize these results by comparing military spouses with the U.S. adult population. To do so, we compared rates from the current study with the 10-year HP2020 national targets, which represent the aims that the government sets at a population level, acknowledging that these comparisons must be interpreted cautiously due to demographic differences between the target population of the Family Study and the U.S. adult population [30]. A higher proportion of military spouses (44.2%) met the HP2020 healthy weight/BMI goal compared with the national target of 33.9%. Relatedly, fewer military spouses were obese (23.7%) compared with the national obesity target of 30.5%. Sixty-eight percent of military spouses met the HP2020 physical activity objective and 42.6% met the strength training objective, higher than the national targets (47.9 and 24.1%, respectively). The proportion of military spouses meeting the sleep objective (61.3%) was lower than the national target of 70.8%. A comparable proportion of military spouses did not meet goal related to risky drinking, compared with the national target (24.3% vs 25.4%). More military spouses reported currently smoking than the national target (20.6% vs 12.0%). Overall, compared with the HP2020 targets for the entire U.S. adult population, a higher proportion of military spouses met the objectives for healthy weight, obesity, and physical activity than the national targets, while fewer met these targets for sleep and smoking. It is unclear to what extent these differences may be explained by the younger age and other demographic differences between this study’s target population and the adult population as a whole. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) does not provide demographic breakdowns for its population targets.

Multivariable results suggest that social support and perceived support from the military are associated with military spouses’ health behaviors. Specifically, spouses who reported being bothered by not having someone to turn to when they were having a problem were less likely to achieve a healthy weight or sufficient sleep and were more likely to engage in risky alcohol use and to smoke cigarettes. Similarly, when spouses perceived greater efforts by the military to support their families, they were more likely to meet the healthy sleep goal. Research suggests that spouses identify multiple ways their military lifestyle makes it difficult to maintain strong social connections, including frequent moves, living far from family and friends, and lack of time [31]. Together, these results suggest providing resources to assist spouses in developing social networks and support, and addressing identified barriers to connectedness, may have broader implications on the overall health and well-being of spouses. Several spouse demographics were associated with health indicators and were controlled for in the multivariable models, including gender, age, ethnicity and education. Additionally, spouses of officers, compared to enlisted personnel, were more likely to meet the weight, aerobic exercise, and tobacco goals and spouses of Air Force members were more likely to meet the sleep and substance use goals compared to Army spouses.

Based on our results, it is clear that service member and spouse health behaviors are associated and likely influence one another bidirectionally. These findings suggest that enhanced support and program for either or both partners may assist the couple and improve family readiness. Although there are many existing social support and military health promotion programs available, most target service members rather than military spouses, and there is a lack of unified family resource programs [32]. Existing family programs include Military OneSource, which disseminates information on all military family health resources; Operation Live Well, an initiative to improve health and wellness for the entire defense community, and its Healthy Base Initiative targeting service members, DoD civilians, and their families. The U.S. Army Public Health Center Performance Triad includes a specific resource page for spouses with educational materials and social media resources that aim to improve sleep, physical activity, and nutrition and operate the Army Wellness Centers that are available to military spouses. Building upon these existing military health promotion and social support programs to be more accessible and targeted to military spouses could have direct implications for increasing positive health behaviors synergistically among service members and their spouses.

Military experiences associated with injury, PCS moves, and family stress were not significantly associated with the health behavior outcomes in this study. Interestingly, having more stressful experiences related to deployment was associated with a greater likelihood of having a healthy BMI. This finding is inconsistent with previous research. For example, Fish and colleagues (2014) found that deployment has no relationship with healthy weight, but that male Army spouses were more likely to be obese or overweight than female spouses [8]. Padden and colleagues (2011) found that deployment was associated with poorer dietary behaviors [33].In the current study, deployment-related stress was associated with only a single health outcome, healthy weight/BMI, and that relationship was fairly weak, suggesting that deployment-related stress and PCS moves may not have a strong or consistent influence across health behaviors. As Family Study follow-up data for this longitudinal effort become available, it will be possible to further investigate these relationships prospectively. Future studies might assess if other military-related stress influences health indicators over time and if there are directional effects in terms of behavioral influence between the spouses in meeting the goals, and if they are stronger from the service member to the spouse or vice versa. Such studies could inform the most effective points of prevention and intervention for military families. Future longitudinal research could also assess more comprehensive bio-psycho-social models predicting health outcomes for military spouses to distinguish the strongest influencing factors, including behavioral health predictors such as Posttraumatic Stress Disorder which has been linked to health outcomes in various studies [34,35,36].

Limitations and strengths

There are a number of limitations to this study that should be considered. The data are largely based on self-report which can be vulnerable to bias, and it would be ideal to also have observational or medical data to validate the health outcomes. However, CDC measures on the national health objectives are also based on self-report, making these measures more comparable. The reports are also retrospective, meaning that spouses and service members reported on their health behaviors over a specified time period (e.g., the last month) and may have experienced poor or biased recall. Additionally, there are missing data, particularly on the item related to PCS stress. Finally, only married couples of the opposite sex were included in the study, thus the results may not generalize to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered spouses or to single-parent households. Despite these limitations, the study has considerable strengths. The cohort includes a representative sample of young military couples across service branches and components, including active duty, military Reserve, and National Guard participants. The study cohort also includes both female and male military spouses and data acquired from both the spouse and service member. The constructed self-report health measures also closely align with the HP2020 objectives, enabling comparisons of military spouses’ health behaviors and national benchmarks.

Conclusions

Using the HP2020 objectives as a framework for identifying key health behaviors and benchmarks, this study identified factors, including military-specific experiences that may contribute to physical health behaviors and outcomes among military spouses. The findings provide important insights that could help inform health promotion programs for military families, improve force readiness and retention, and enhance the well-being of military families. The study also offers a unique contribution to the HP2020 efforts by revealing the proportion of military spouses, a large and important segment of the population, who meet several key health objectives.

The spouses in this study face similar challenges in maintaining a healthy lifestyle as individuals in the broader civilian population, but they must also navigate additional stressors related to their role as part of a military dyad. These stressors may include having a spouse who is deployed, not having a strong social support system, and not feeling supported by the military. It is important that these spouses are provided with the support services and programs to help them maintain and improve their health behaviors and improve the overall health and well-being of U.S. military personnel.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available; deidentified data are available upon the establishment of a Department of Defense data use agreement.

Abbreviations

- APHC:

-

Army Public Health Center

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- DoD:

-

Department of Defense

- Family Study:

-

Millennium Cohort Family Study

- HP:

-

Healthy people

- PCS:

-

Permanent change of station

References

U.S. Department of Defense. Department of Defense Instruction 1010.10: Health promotion and disease prevention. http://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/101010p.pdf. Published April 28, 2014. Accessed 20 Mar 2018.

Dall TM, Zhang Y, Chen YJ, et al. Cost associated with being overweight and with obesity, high alcohol consumption, and tobacco use within the military health system's TRICARE prime-enrolled population. Am J Health Promot. 2007;22(2):120–39.

Barlas FM, Higgins WB, Pflieger JC, et al.; ICF International. 2011 Health Related Behaviors Survey of Active Duty Military Personnel. https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Access-Cost-Quality-and-Safety/Health-Care-Program-Evaluation/Survey-of-Health-Related-Behaviors/2011-Health-Related-Behavior-Survey-Active-Duty. Published February 2013. Accessed 20 Mar 2018.

Institute of Medicine. Substance use disorders in the U.S. Armed Forces. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013.

Leigh JP. Economic burden of occupational injury and illness in the United States. Milbank Q. 2011;89(4):728–72.

Eaton KM, Hoge CW, Messer SC, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems, treatment need, and barriers to care among primary care-seeking spouses of military service members involved in Iraq and Afghanistan deployments. Mil Med. 2008;173(11):1051–6.

Kennon J. Nutrition plan. Paper presented at: 2012 Performance triad nutrition action plan workshop; September 2012, 2012; Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD.

Fish TL, Harrington D, Bellin MH, Shaw T. The effect of deployment, distress, and perceived social support on Army spouses’ weight status. US Army Med Dep J. 2014:87–95.

Nice DS. The course of depressive affect in navy wives during family separation. Mil Med. 1983;148(4):341–3.

Steenkamp MM, Corry NH, Qian M, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in United States military spouses: the millennium cohort family study. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(9):815–29.

Trone DW, Powell TM, Bauer LM, et al. Smoking and drinking behaviors of military spouses: findings from the millennium cohort family study. Addict Behav. 2018;77:121–30.

Koh HK. A 2020 vision for healthy people. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(18):1653–6.

Healthy People 2020. National Center for Health Statistics website. https://wwwcdcgov/nchs/healthy_people/hp2020.htm. Updated October 14, 2011. Accessed 20 Mar 2018.

Black LI, Nugent CN, Vahratian A. Access and utilization of selected preventive health services among adolescents aged 10–17. NCHS Data Brief No. 246. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db246.pdf. Published May 2016. Accessed 20 Mar 2018.

Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Race/ethnicity, gender, and monitoring socioeconomic gradients in health: a comparison of area-based socioeconomic measures—the public health disparities geocoding project. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1655–71.

Martinez ME, Ward BW, Adams PF. Health care access and utilization among adults aged 18–64, by race and hispanic origin: United States, 2013 and 2014. NCHS Data Brief No. 208 https://wwwcdcgov/nchs/data/databriefs/db208.pdf. Published July 2015. Accessed 20 Mar 2018.

Smith KB, Humphreys JS, Wilson MGA. Addressing the health disadvantage of rural populations: how does epidemiological evidence inform rural health policies and research? Aust J Rural Health. 2008;16(2):56–66.

Wilson PA, Yoshikawa H. Improving access to health care among African-American, Asian and Pacific islander, and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. In: Meyer IH, Northridge ME, editors. The health of sexual minorities. Boston, MA: Springer; 2007. p. 607–37.

Bray RM, Hourani LL, Olmsted KLR, et al. 2005 Department of Defense Survey of health related behaviors among active duty military personnel: a component of the defense lifestyle assessment program (DLAP). http://www.dtic.mil/get-tr-doc/pdf?AD=ADA465678. Published December 2006. Accessed 20 Mar 2018.

Kress AM, Hartzell MC, Peterson MR, et al. Status of US military retirees and their spouses toward achieving healthy People 2010 objectives. Am J Health Promot. 2006;20(5):334–41.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and improving health. https://wwwhealthypeoplegov/2010/Document/pdf/uih/2010uih.pdf. Published November 2000. Accessed 20 Mar 2018.

Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(4):370–9.

Taylor MK, Markham AE, Reis JP, et al. Physical fitness influences stress reactions to extreme military training. Mil Med. 2008;173(8):738–42.

Padden DL, Connors RA, Posey SM, et al. Factors influencing a health promoting lifestyle in spouses of active duty military. Health Care Women Int. 2013;34(8):674–93.

Rivera LO, Ford JD, Hartzell MM, Hoover TA. An evaluation of Army wellness center clients’ health-related outcomes. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(7):1526–36.

Aljasir BA, Al-Mugti HS, Alosaimi MN, et al. Evaluation of the National Guard Health Promotion Program for chronic diseases and comorbid conditions among military personnel in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia, 2016. Mil Med. 2017;182(11–12):e1973–80.

McMaster HS, LeardMann CA, Speigle S, et al. An experimental comparison of web-push vs. paper-only survey procedures for conducting an in-depth health survey of military spouses. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):73.

Crum-Cianflone NF, Fairbank JA, Marmar CR, et al. The millennium cohort family study: a prospective evaluation of the health and well-being of military service members and their families. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2014;23(3):320–30.

Corry NH, Williams CS, Battaglia M, et al. Assessing and adjusting for non-response in the millennium cohort family study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17:16.

Healthy People 2020 [database online]. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; December 2017. https://www.healthypeople.gov/. Accessed 2 Feb 2018.

Mailey EL, Mershon C, Joyce J, Irwin BC. “Everything else comes first”: A mixed-methods analysis of barriers to health behaviors among military spouses. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1013.

Clark MG, Jordan JD, Clark KL. Motivating military families to thrive. Fam Consum Sci Res J. 2013;42(2):110–23.

Padden DL, Connors RA, Agazio JG. Determinants of health-promoting behaviors in military spouses during deployment separation. Mil Med. 2011;176(1):26–34.

Bartoli F, Crocamo C, Alamia A, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of obesity: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(10):e1253–61.

Saladin ME, Brady KT, Dansky BS, Kilpatrick DG. Understanding comorbidity between PTSD and substance use disorders: two preliminary investigations. Addict Behav. 1995;20(5):643–55.

Lamarche LJ, De Koninck J. Sleep disturbance in adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(8):1257–70.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the other contributing members of the Millennium Cohort Family Study Team from Abt Associates, including Tara Earl, PhD; Samantha Karon, BA Christopher Spera, PhD; and Elle Gault; as well as members from the Deployment Health Research Department, Naval Health Research Center, including Lauren Bauer, MPH; Carlos Carballo, MPH; Alejandro Esquivel, MPH; Cynthia LeardMann, MPH; Hope McMaster, PhD; Jackie Pflieger, PhD; and Evelyn Sun, MPH. The authors gratefully acknowledge the members of the Millennium Cohort Family Study Team from the Center for Child and Family Health, including Ernestine Briggs-King, PhD; Ellen Gerrity, PhD; Robert Lee, MS; Robert Murphy, PhD; and Angela Tunno, PhD. In addition, the authors express their gratitude to the Family Study participants, without whom this study would not be possible.

Funding

This work was funded to be completed by Abt Associates under Contract #W911QY-16-C-0089, supported by the Naval Health Research Center. The study team at the Naval Health Research Center collected and cleaned the data under the direction of Dr. Valerie Stander, who participated in this study as a co-author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NC assisted in the development of the analytic plan, led the drafting of the manuscript, coordinated the study, and helped interpret findings. SR conducted the data cleaning, coding, and analysis. CW helped conceptualize the analytical plan and oversaw all analyses. AS helped develop the study concept and contributed to drafting the manuscript. KW provided input into the analytical plan, helped interpret findings, and assisted in manuscript development and review. JF reviewed the manuscript and provided insight into the results and discussion. VS provided input on the analytic plan, helped interpret findings, and provided critical feedback and revisions to the manuscript. All authors have read and approve the manuscript.

Authors’ information

Disclaimer: I am a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of my official duties. Title 17, U.S.C. §105 provides that copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government. Title 17, U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties.

Report No. 18–39 was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command under work unit no. N1240. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was overseen and approved by the Naval Health Research Center’s Institutional Review Board (Protocol 2000.0007) and the Office of Management and Budget (approval number 0720–0029). Written or electronic informed consent was obtained for all participants. This research has been conducted in compliance with all applicable federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects in research (Protocol NHRC.2015.0019).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Corry, N.H., Radakrishnan, S., Williams, C.S. et al. Association of military life experiences and health indicators among military spouses. BMC Public Health 19, 1517 (2019). https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.1186/s12889-019-7804-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.1186/s12889-019-7804-z